Unfalsifiability

An argument presented in a form such that it can never be shown to be false.

An unfalsifiable argument can be qualified and amended at will. For instance, the statement “faith can move mountains” is unfalsifiable: if you cannot move mountains, that only shows that you haven’t enough faith. Empty abstractions about destiny, vision and optimism cannot be refuted; they can only be dismissed as meaningless. The philosopher Karl Popper summarises:

It is the possibility of overthrowing [a theory], or its falsifiability, that constitutes the possibility of testing it, and therefore the scientific character of a theory.U1

Despite Popper’s advice, unfalsifiable statements are popular. Examples:

-

The developing countries would all become thriving market economies if only the West would give them enough aid.

-

The reason our reforms haven’t yet produced the promised results is that they haven’t gone far enough.

-

Economic growth will eventually make us all happier.

-

If we would only get round a table and talk to them, and build hospitals and schools, the violence would stop.

-

All we need is for everyone to be as softly-spoken and peace-loving as me—then there would be no violence in the world.

-

There is a rhinoceros in this room, but of a kind that you cannot see, touch, smell, taste or hear.

-

The reason we haven’t achieved heaven on earth yet is because we haven’t eliminated enough dissidents.

-

(the Freudian version) “The woman you were dreaming about was your mother.” “No, it wasn’t!” “Now you’re getting angry: that proves it was your mother.” “Oh, all right, then.” “You see. . . ?”U2

A famous instance of the constantly-revised argument is the model of planetary motion developed by the astronomer Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaeus, c.100–178). Having placed the Earth at the centre of the solar system, all he needed to do to reconcile this with the evidence was to design a complex set of cycles and epicycles: with every new observation, new elaborations could be added.U3

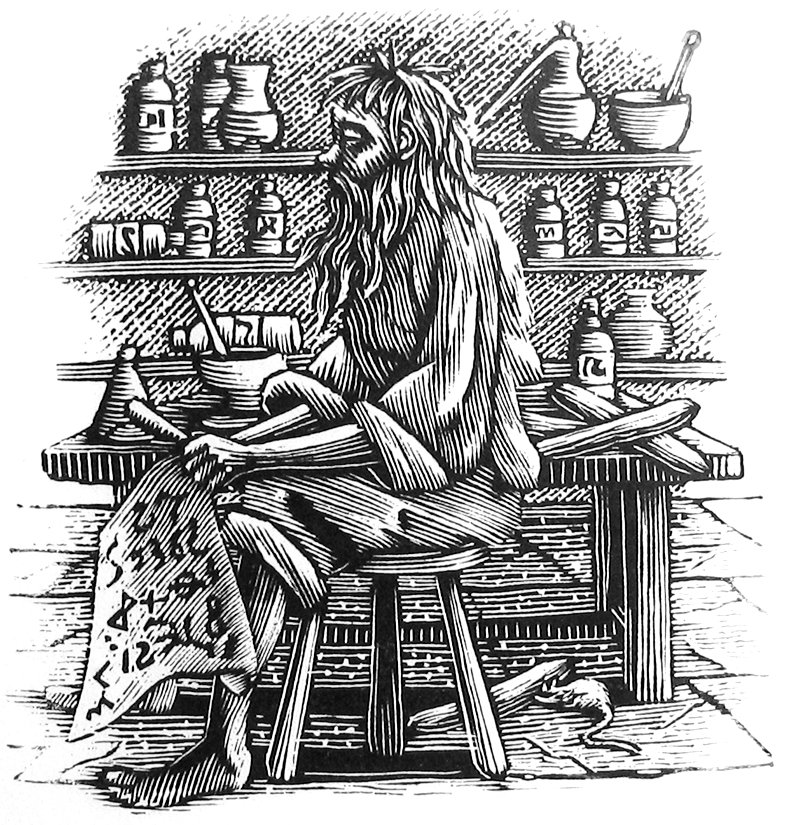

And we have a happy example from Jonathan Swift: on his visit to the Grand Academy of Lagado, Gulliver was introduced to a scientist working on technologies for renewable energy,

He had been eight years upon a project for extracting sun-beams out of cucumbers . . . He told me, he did not doubt, in eight years more, he should be able to supply the Governor’s gardens with sunshine at a reasonable rate; but he complained that his stock [funding] was low, and entreated me to give him some as an encouragement to ingenuity.U4

The idea that one more heave is all that is now needed is hard to disprove, even by experiment: if it is successful, that shows you were right; if it is unsuccessful, that shows that all that is needed is one more heave. Given that the required heave is the one that is now, the argument is unfalsifiable. If you impose a big idea but can constantly reform and fix it if it goes wrong, you never have to face up to the possibility that there could be something wrong with the idea.

And here are some more cases that invite unfalsifiability:

1. Very large projects—such as super-giant water projects, or revolutionary change in schools, health services or constitutions—change the mental map: any argument that follows has to accept the premises imposed on it by the accomplished fact. There is no way back.

2. Elusive certainty: if you insist that no criticism of your argument can be admitted unless it comes wrapped in certainty proved beyond scientific dispute, it is secure against critics.

3. In a crisis, your empty proposition can be claimed to be the only hope, placing it beyond criticism.

4. It may be the only ethical solution, obscuring the fact that it is impossible.

5. The argument, or assumption, may be integral to the person’s belief in herself and in her own existence, so that a change of mind is impossible.

6. The idea may be so desirable—sunbeams to order—that to give up on it would break your heart.U5

Related entries:

Sunk Cost Fallacy, Self-Evident, Kaikaku.

« Back to List of Entries