Responsibility, The Fallacy of

The fallacy that intervention is necessary to make a system work.

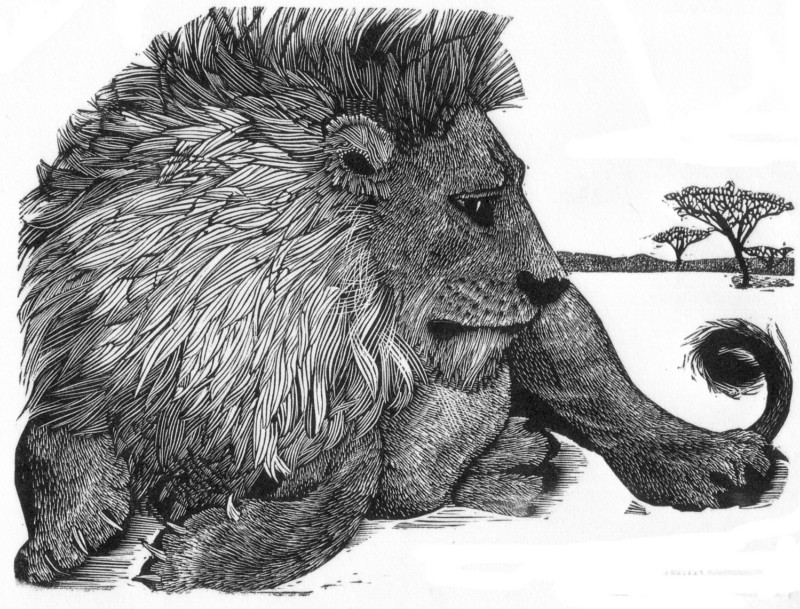

A natural system does not, in general, require its participants to make any effort to sustain it. On the contrary, stability is maintained by the pursuit of self-interest. Lions eat antelopes; antelopes show every sign of being opposed to this arrangement; the system of lions, antelopes and the ecology they support nevertheless thrives without their volition. The reason for that outcome is that the system is governed by rules—such as the laws of thermodynamics—which guide, or frustrate, intentions. And, in general, the rules governing systems do not only bring stability; just a few simple rules can lead to the emergence of startling complexity and diversity.R64

However, when this is applied to human society, there is an obvious snag. Whereas the rules which limit the ability of antelopes and lions to have their way are not made by the participants themselves, those which shape human society must to a large extent be made by the people who will then be constrained by them. What, then, are the constraints or rules that provide a foundation for stability and emergence in the case of human society?

The self-evident answer is “laws”. It is, however, the wrong answer. It is the function of laws to enable a society to do what it wants—to grow, and to fulfil expectations—with the least possible constraint and dissidence: if antelopes could legislate, the first law they would pass would be one that outlawed lions. Laws do, of course, define rules and set up sanctions to enforce them, but the nature of the human society which makes the laws is derived from somewhere else.

It comes from the physical facts of land and climate, from history, custom and social capital; it comes from the moral deliberation and invention which can modify these inheritances for better or for worse. It comes from tradition—the expressive and significant narrative which identifies a community as particular and makes it intelligible; it comes from a perceptive engagement with the natural environment; it comes from the communitarian ethic conferred by practice; and it comes from play, which learns, teaches, reinforces and gradually revises the traditions. If these grid-lines—providing a frame of reference beyond immediate opportunism—were removed, the broken-backed community or state would indeed need someone to take over “responsibility”.R65

And it is when we start trying to take responsibility ourselves for the services which were once freely provided by a healthy system that we begin to realise how valuable that provision was. Here are some of the things that were once substantially supplied for free by the vernacular, products and gifts of both social systems and natural systems: self-policing communities and secure social foundations for law and order; public participation in politics and an ability to sustain debate with comparatively little risk of it deteriorating into faction; the competence of households in teaching children to speak, to know what conversation means, to be socialised; a stabilised climate; conserved fertility and micronutrients in the soil; abundant marine fisheries.

The point is not that these things were done perfectly but that, in spreading patches of systems breakage, they are now not being done at all. Filling the gaps becomes someone’s responsibility at about the same time as it becomes impossible. Responsibility can be a sign of trouble.R66

Related entries:

Constructivism, Leverage, Encounter, Place.

« Back to List of Entries