Eroticism

Our society fills much empty space with thoughts of sex, yet it is not comfortable with the erotic. Far from integrating it into its culture, it buries it deep in the private sphere—a personal matter, like remembering to take your medication. At the end of the road we are travelling on, desire will be not a hunger to be celebrated, but an issue to be sorted.

The erotic is an energy source. Its energy is desire—intense, beyond your own control and intention, and unsafe, like a cliff path without a handrail. You lack detachment: you are there, right at the edge. This is not your territory: you are on the lip of someone else’s. Lean Logic argues that this energy feeds into—gives intensity to—all our other emotions. The erotic is the dazzling power supply, the soular energy, on which we depend for the whole of our emotional lives.

At its heart is the possibility of a gift. Things that you take are more-or-less under your control and, to that extent, lack excitement. Things that you are given have an independent life of their own: you can never be quite sure that they will come your way, nor that, if they do, they will be the real thing, nor that what you give back is as real as what you receive. But you live in hope on all these, aware that this garden will yield its reciprocal gifts only if it is cultivated and watered and walked in:

Mane surgamus ad vineas, videamus si floruit vinea, si flores fructus parturiunt, si floruerunt mala punica: ibi dabo tibi ubera mea.

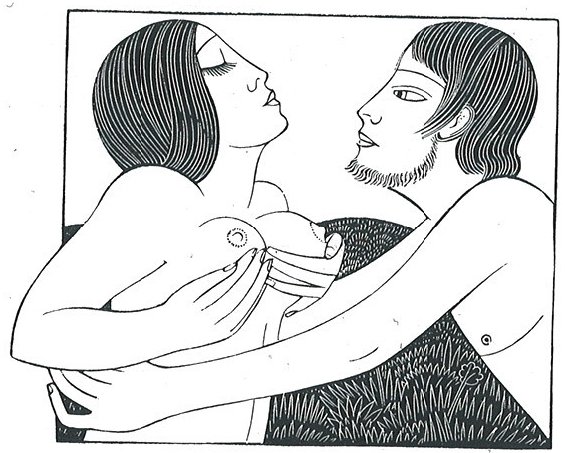

Let us rise up early and go to the vineyards; let us see if the vine flourish, whether the tender grape appear, and the pomegranate are ripening: there will I give thee my breasts.198

Eric Gill gives us an engraving of this, called “Ibi Dabo Tibi”.

This sense of giving and surrender irrigates every other aspect of our culture. The extent to which we enter into a Corot landscape or a Vermeer household is the extent to which we surrender ourselves to them. The English poet George Herbert was intent on surrender, seeming not to mind too much whether it was to a woman or to God. He needed the erotic. He knew . . .

. . . the ways of pleasure; the sweet strains,

The lullings and the relishes of it;

The propositions of hot blood and brains;

What mirth and music mean . . .

George Herbert, The Pearl, 1633.199

. . . and here is Richard Crashaw being rather carried away, it seems:

Lord, when the sense of thy sweet grace

Sends up my soul to seek thy face.

Thy blessed eyes breed such desire,

I dy in love’s delicious Fire.

Richard Crashaw, A Song, 1652.200

We have this idea, too, in the mystic tradition of Islam—Sufism—intoxicated with love, living with ecstasy, for which . . .

. . . the soul needs the wings of human love to fly toward divine love; [it is] the ladder leading to the love of the Merciful.201

And this is also the unlikely location of medieval monasticism, empowering with erotic energy a multinational institution designed for spiritual observance, care of those in need, education, publishing, archiving and population control. Although the monks and nuns of that long-lived tradition did in some ways “leave the world upon a shelf” as Chaucer observed in The Canterbury Tales, the principle was: do not repress energetic drives such as sex; use them as the energy source for talent, love and hard thinking, but set them in a different context.202 There was, it is true, an evident risk of failure and compromise in redirecting these drives from the erotic love of people to loving God, but the monastic discipline was skilful and experienced: it knew how to handle large resources of emotional energy—and how to contain it within the context of music and poetry, the graphic arts and prayer, architecture, charity, philosophy, community building, and that daily workout for the emotions provided by the Psalms (see “Feeling Better?” below).203

|

FEELING BETTER? The emotional capital of Western culture is, in part at least, a gift from its religion—and the spectrum of emotion is clearly visible in the Psalms, composed for ritual which contains and socialises the difficult emotions—violence, vengeance, betrayal, yearning, lament. In the thin rituals of the market, this full-blooded recognition of the “bad” emotions—along with the “good” ones—is censored and discarded. But if only the good emotions are permitted, the bad ones develop unsupervised: the possibility of recognising them and of learning how to handle them closes down. Better to celebrate them. Delight: Then was our mouth filled with laughter: and our tongue with joy. 126:2 Vengeance: O daughter of Babylon, wasted with misery: yea happy shall he be that rewardeth thee, as thou hast served us. Blessed shall he be that taketh thy children and throweth them against the stones. 137:7–9 Sickness: I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint: my heart also in the midst of my body is even like melting wax. My strength is dried up like a potsherd, and my tongue cleaveth to my gums: and thou shalt bring me into the dust of death. 22:14–15 Desire: Like as the hart desireth the water-brooks: so longeth my soul after thee O God. 42:1 Anger: Let their eyes be blinded that they see not: and ever bow thou down their backs. Let them be wiped out of the book of the living. . . . That thy foot may be dipped in the blood of thine enemies: and that the tongue of thy dogs may be red through the same. 69:24,29; 68:23 Displeasure: Let hot burning coals fall upon them: let them be cast into the fire and into the pit, that they never rise up again. 140:11 Love: Whither shall I go then from thy Spirit: or whither shall I go then from thy presence? If I climb up into heaven, thou art there: if I go down to hell thou art there also. If I take the wings of the morning: and remain in the uttermost parts of the sea; Even there also shall thy hand lead me: and thy right hand shall hold me. 139:6–9 Pleasure: That he may bring food out of the earth, and wine that maketh glad the heart of man: and oil to make him a cheerful countenance, and bread to strengthen man’s heart. 104:15 Saving the day: He chose David also his servant: and took him away from the sheep-folds. 78:69 |

The result could not be described as repressed: the aim, wrote the twelfth century scholar Hugh of St. Victor, was “to see what the untutored eye does not see, and to form desire”, by subjecting oneself to authority and learning how to recognise virtue—in short, learning to master a skill, to love your subject and get emotional about it.204 “Tears of desire for heaven” were positively encouraged; emotional energy was recognised as a reserve, waiting to be tapped.205

It was an emotional training which lasted into the seventeenth century, and one way of keeping in trim was to do the programme of Spiritual Exercises which had been devised by St. Ignatius Loyola: four weeks of contemplation of the Life, Passion and Resurrection of Christ could wake the soul from its torpor and make “the south wind blow over the garden of the soul”, bringing the tears of intense affection.206

The Judaic-Christian is—perhaps this is its most astonishing quality—a culture of emotional depth. This is not mysticism; it is not ascetic; it is no exercise in willpower and self-control. On the contrary, it celebrates the passions. The Passion is a story of wringing emotion: pain, grief, love, derision, resolution. It consists almost entirely of emotional events and expression, as Bach demonstrated when he set it to music. The narrative (or poetic) truth is about a raising from the dead, but there is some direct material truth in there too, for love—being the source of emotional life—can claim, rather more literally, to do the same thing. Richard Crashaw summarises this in a three-line request, confident of his answer:

O let that love which thus makes Thee

Mix with our low mortality,

Lift our lean souls . . . .

Richard Crashaw, Lauda Sion Salvatorem, 1652.207

A culture which contains such emotional energy makes it available for the relationships between the people who live there, for the common purpose of making and sustaining community, and it celebrates this private good in the public sphere. All animal behaviour is driven by the emotions, so it is a good idea to keep them fit and well, observant and in training for their life on the edge between us and everything else. The erotic is but one emotion among many, but maybe it is the deepest and most ancient one, and, for Lean Logic, it is the critical energy source for all others. Emotions know the ways of pleasure, the lullings and the relishes of it, the proposition of hot blood and brains, what mirth and music mean. Erotic energy is their blood supply.208

Related entries:

Encounter, Play, Invisible Goods, Spirit.

« Back to List of Entries